Scaling Monosemanticity Extracting Interpretable Features from Claude 3 Sonnet

Scale SAE to Claude 3 Sonnet

Read Paper →They learned a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) on the middle layer of the Claude 3 Sonnet residual stream. They trained three SAEs on the middle layer residual stream: one with 1 million features, one with 4 million features, and one with 34 million features.

Are the Learned Features Interpretable?

First, they manually chose some features and explained them. Then, they used automated interpretability methods to check whether most features are interpretable or not.

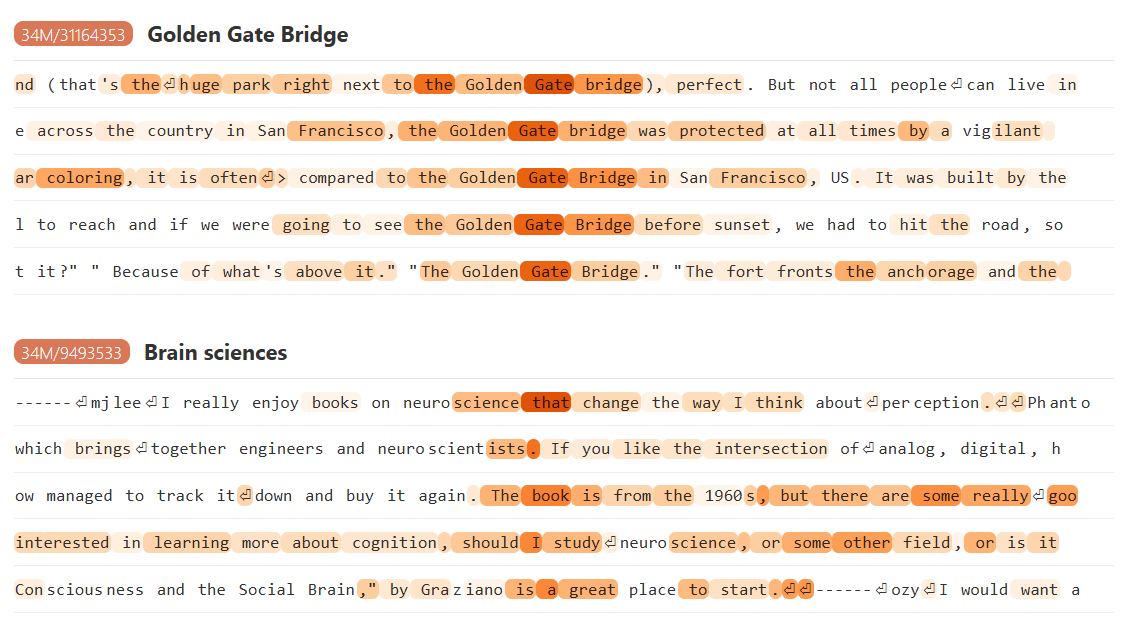

Manually Chosen Features

They chose two features, which they called the “Golden Gate” feature and the “Brain Sciences” feature. They didn’t mention how these two features were identified.

By investigating sequences that highly activate these two features, we can see that they are probably correct about the functionality of these features.

The Causal Effect of Features

They also found that if they increase the activation of one feature, the model is more likely to use that concept in its response. For example, if they boost the Golden Gate feature to ten times its maximum value in the training set, the model self-identifies as the Golden Gate Bridge!

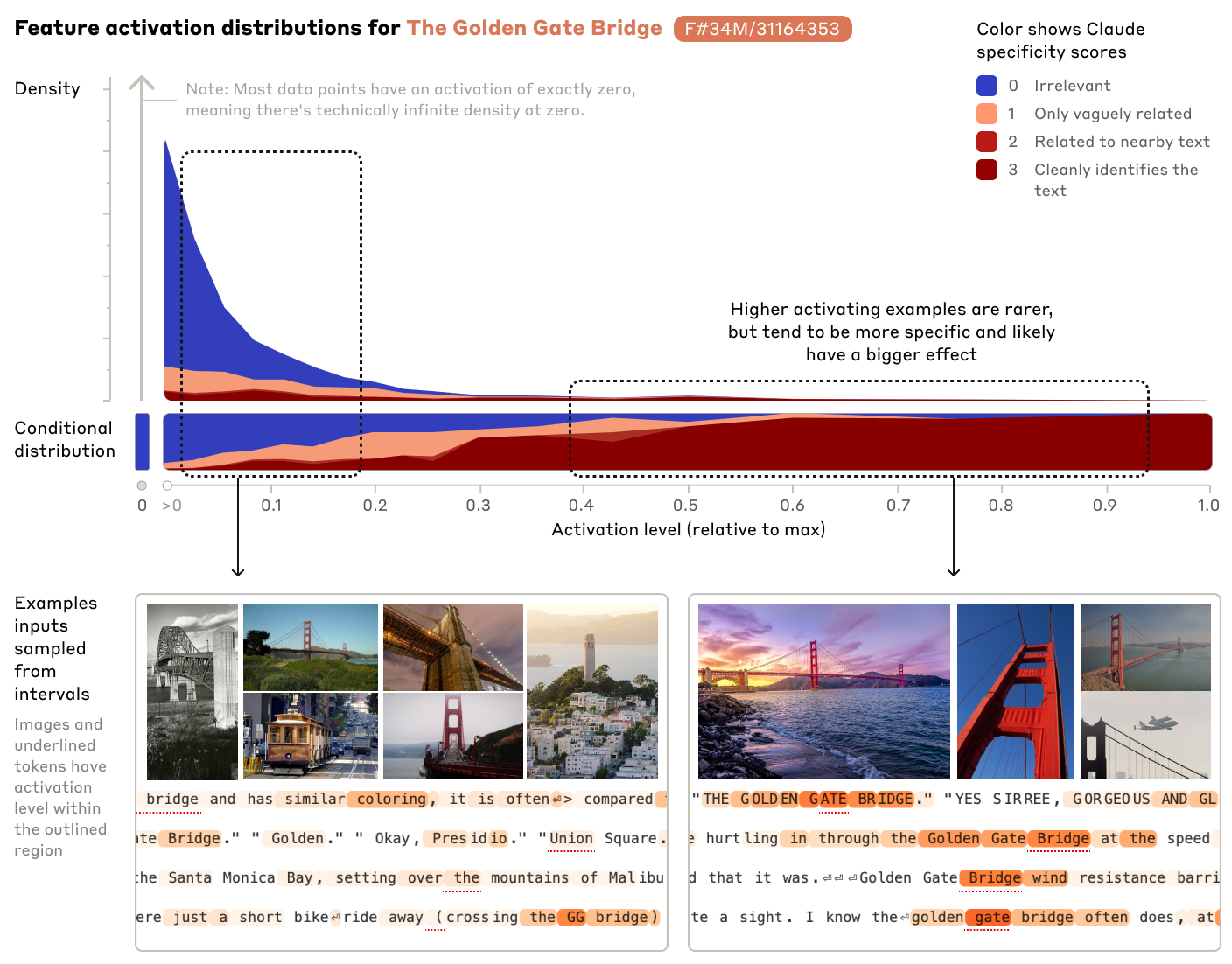

Automated interpretability

They first generate the feature using a large language model (LLM). They provide the model with many examples that activate that feature and ask the model to determine a common characteristic, which becomes the feature name. Then, they evaluate this by scoring the description using different samples that activate this feature. More specifically, they provide the sample and feature description to Claude Opus and ask it to score the relatedness on a scale of 0 to 3. They observed that Opus assigns a score of 3 to most of the samples that strongly activate the feature, and as the sample activates the feature more, the score also increases.

More Complex Features

There are also more complex features, such as the “code error” feature. They tested this feature and observed that it activates on code errors in different languages. It did not activate on typos in text. More specifically, they found instances of it activating for:

- Array overflow

- Asserting provably false claims (e.g., 1 == 2)

- Calling a function with a string instead of an integer

- Division by zero

- Adding a string to an integer

- Writing to a null pointer

- Exiting with a non-zero error code

They also conducted an experiment similar to the Golden Gate cause-and-effect test. When they boosted the feature to a large value and asked the model to predict the output of a correct Python code, the model responded with an error message.

Unable to Identify All Features Even with 34M SAE

They manually tested and confirmed that the model recognizes all London boroughs when asked. However, they could only find features corresponding to about 60% of the boroughs in the 34M SAE. In more detail, they choose a concept like “The physicist Richard Feynman”. They pass it to the model and observe which features are activated. They select the top five features and use the automated interpretability pipeline to generate a description for each one. Then, a human evaluator judges whether this description matches the concept (Richard Feynman). They found that when a feature becomes less frequent in the training set, it is more likely that the SAE cannot identify it and incorrectly assign another feature to it.

Feature Visualization

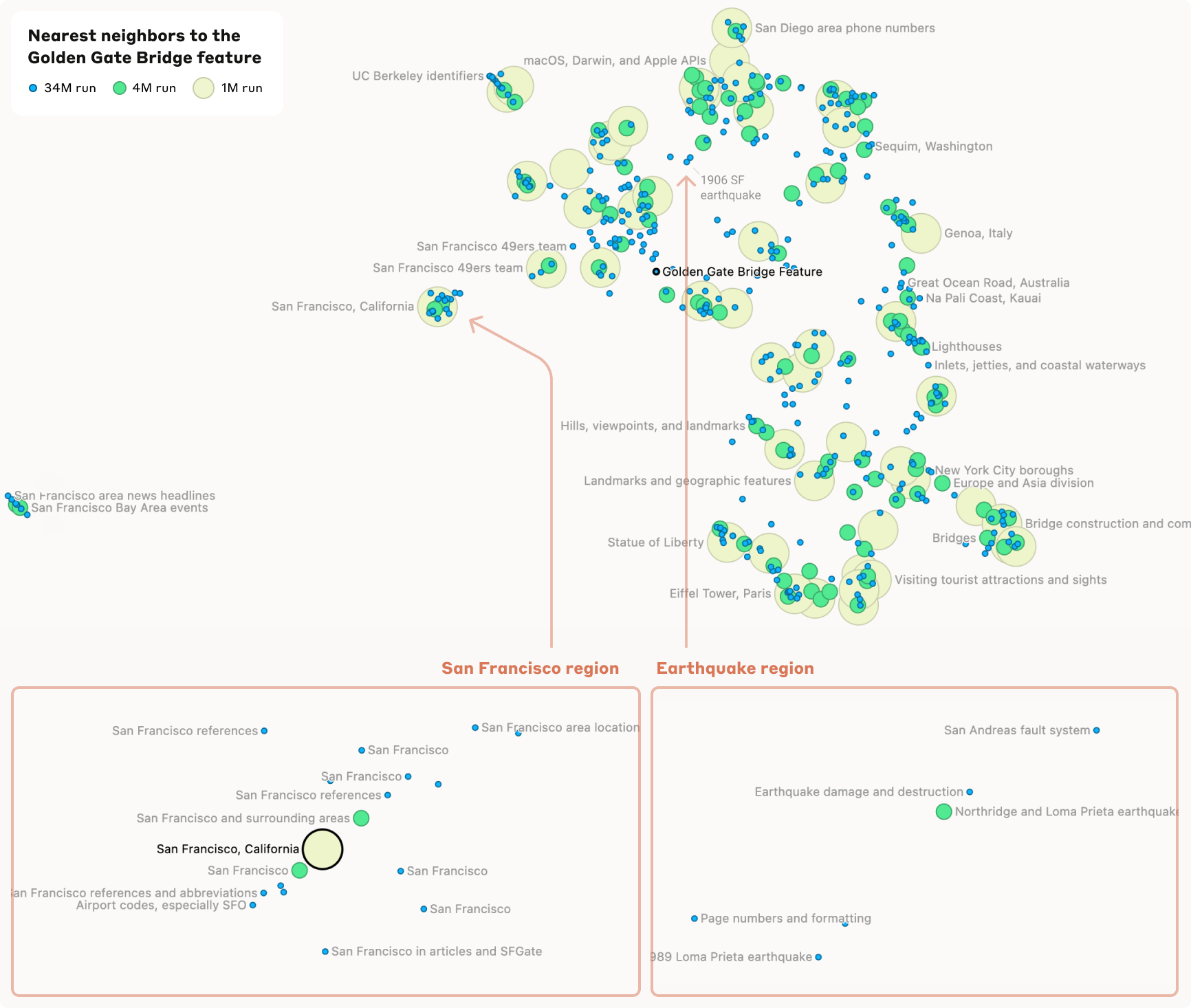

Since they learned more than 34 million features, they needed to find a way to properly visualize them. They used cosine similarity of feature vectors in the learned encoder. Using this method, they chose neighboring features and plotted them using UMAP in 2D.

As you can see, most features are related to the Golden Gate Bridge.